After years of Covid lockdowns, a regulatory crackdown on its biggest technology firms and a worrying decline in its property market, some fear this could mark the start of the ‘Japanification’ of China.

In the 1990s, Japan faced an extended period of deflation, sluggish economic growth and asset value declines as the country painfully deleveraged after an asset price bubble in what some label as its ‘lost decade’.

Now economists are suggesting China could be facing a similar predicament as it grapples with its own bout of deflation, slowing economic growth and structural headwinds like an ageing population.

Despite being the driver for Asian and emerging market growth for many years, if China does face ‘Japanification’, investors may start to reassess their China exposure.

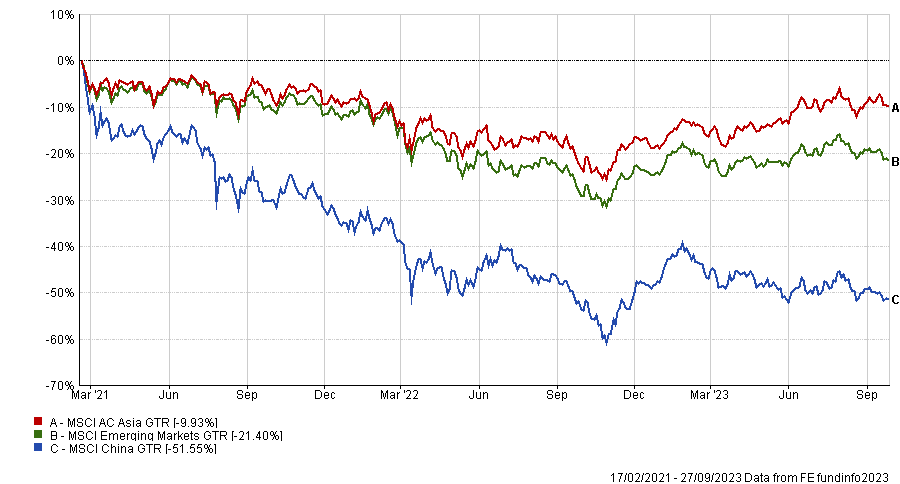

If its equity market is any indication of China’s economy, it has yet to show any signs of recovering after falling over 50% from its peak in early 2021.

But although there are many qualitative similarities between Japan at the start of its ‘lost decade’ and China today, the actual economic growth figures and official forecasts for China tell a different story.

Between 1993 and 2003, Japan’s economic growth was 1.14% annually, well below many other developed economies. The Chinese government on the other hand has set a target to double GDP by 2035, implying annual GDP growth of 4.6%.

Clement Chong, head of credit research at Eastspring Investments, said: “China is not facing negative growth; it is still growing. The question is how much it will grow by.”

“It is just not as fast as many had hoped and the market is simply resetting expectations.”

In 2023, China is expecting economic growth of roughly 5%. Despite being less than the 6% GDP growth it experienced in the previous decade, it is far ahead of this year’s GDP growth forecast of 3% globally, 2% in the US and less than 1% in the Eurozone.

“The Chinese authorities are also quite data-dependent,” Chong added. “They are still sticking to their GDP growth target in our view, so if there is any weakness in their economy, they will put forward supportive policies.”

He continued: “We are seeing a bit more urgency in the way that policymakers are reacting to the data they are seeing in the market.”

One example of recent support from Chinese authorities is the loosening of policies relating to the property sector in tier 1 cities. Chong said: “That’s the kind of policy we wouldn’t have imagined seeing five years ago.”

He also explained that investors need to realise that demand is slowing down globally, not just in China: “They are experiencing a slowdown also because of what is happening in global markets.”

‘Japanification’ is very unlikely

Despite its ambitious growth target, the recent policy support from Chinese authorities will push GDP growth close to its official target this year, according to a recent outlook report by UBS Global Wealth Management’s chief investment office.

“Though a structurally slower growth pace is almost certain in the years to come, we think a prolonged period of outright stagnation – or “Japanification” – is very unlikely,” the authors said.

“In fact, our forecasts still see China accounting for around one-third of global economic growth this decade.” The authors also added that China’s intention to double its GDP by 2035 was a “tough but achievable target”.

So even though China’s growing debt pile, ageing demographics and ongoing geopolitical pressures will no doubt change its growth trajectory, UBS Wealth Management still expects the world’s second largest economy to grow GDP an average of 4% to 4.5% over the next decade.