The investment company’s founder and chief executive, Xiaolei Zhang, handed himself into police on 27 December in Nanjing, which lies just over 1,000km south of Beijing.

Described as a cult by a former executive, Qianbao, also known at Qbao, translates into “money treasure”.

Before it was shut down, a statement on Qbao’s website read: “Company owner Zhang has been put in custody for suspicion of illegal fundraising crime. Police are calling on Qbao investors in all regions to report to local public security authorities and co-operate in investigations,” reports local newspaper Caixin.

The scam

The company offered returns of up to 80% after people invested a minimum sum and took part in promotional activities; such as watching adverts, sharing information, or simply signing into their Qbao account on a daily basis.

Many investors reportedly borrowed heavily from banks and online lenders to invest with the company. A 26-year-old told Caixin that he had applied for seven credit cards to fund his Qbao investment.

Pervasive Ponzis

Qbao’s failure also mimics a similar scheme that was shut down by Chinese authorities in 2017. Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platform Ezubao cheated 900,000 investors out of CNY50bn.

The architects of the scam were sentenced to life in jail.

In July, tens of thousands of members of a different Ponzi scheme took to the streets in protest after the government said their scheme was illegal and arrested its founder, Tianming Zhang, understood to be of no relation.

They were reportedly protesting against the government’s investigation and not to denounce the scam into which some had poured their life savings.

At the time, an academic at the Renmin University of China said that Ponzi schemes remain rife in China because of financial naivety and a collective desire for unfeasibly high returns.

Cult following

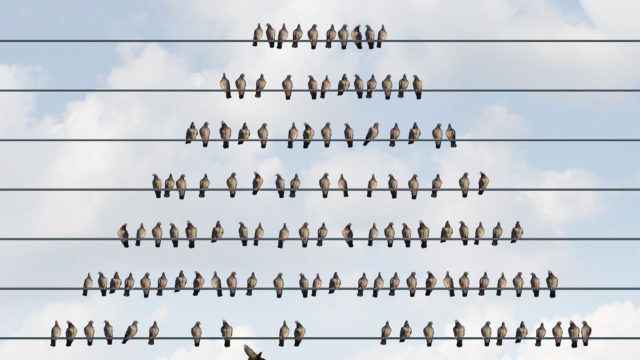

State-owned English language newspaper Global Times, reported that Qbao had cultivated a large number of supporters, known as Baofen, who have not only invested money but also sworn continuous loyalty and support to Zhang.

Aidan Yao, senior emerging Asia economist at Axa Investment Managers, told FSA‘s sister publication International Adviser that he wouldn’t be surprised to see even more schemes in coming years, as some of the people using the site were “driven purely by financial naivety and a gambling mentality”.

Yao’s understanding is that “Qbao does not have a tangible business to support the extraordinary return it promised to pay users”.

Some people were using it as a wallet for online shopping, with similar services available through Alibaba and Tencent. Others, however, “are in it for more speculative gains, attracted by Qbao’s extraordinary return promises or easy money-marketing tasks”, he explained.

Yao has heard rumours that people could make a decent living just by performing simple tasks, such as reading advertisements.

“The government started to tighten these online financial platforms and P2P sites last year. But it will take time to raise the average level of education of Chinese investors, I’m afraid.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see more Qbao and Ezubao in the coming years, because, sometimes, making painful mistakes is the best way to learn,” Yao said.