As central banks around the world continue to grapple with rising prices, this overlooked crucial global commodity might threaten to cause future bouts of inflation, according to Shehriyar Antia, vice president and head of thematic research at PGIM.

“Food is the most overlooked and least appreciated major macro factor,” he said. “It accounts for 40% of global employment across the world and governments spend so much on it supporting farmers and prices.”

The amount that governments globally spend on supporting agriculture has reached $817bn annually, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Yet despite its macroeconomic importance, Antia argues that food and the supply chains that support it are becoming more and more vulnerable.

He believes it poses a unique threat to global investors, creating an underappreciated risk, which will become more prevalent going forward.

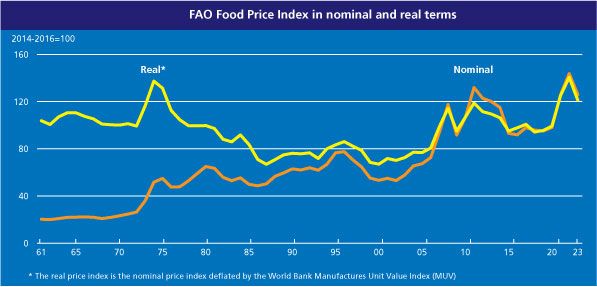

Although food prices have fallen from their recent peaks, they remain at historical highs because of frequent extreme weather events and volatile oil prices increasing the cost of producing and transporting food.

Aside from the direct impact on overall consumer price index figures across different economies, Antia argues there are more overlooked risks posed by food inflation.

“Food inflation hits differently,” he said. “When someone has to spend more to feed a family, they have less money to spend on clothes, on vacations and on other items, so food inflation can really drive consumption patterns.”

Additionally, since food inflation is very unpopular politically, he argued that often governments respond so strongly to it that can impact fiscal budgets.

The International Monetary Fund said in a report earlier this year that governments should use fiscal policy to protect the most vulnerable from food and energy price spikes.

As such, when these bouts of inflation happen it either gets expressed in the price consumers pay, or it gets expressed in fiscal deficits where there are subsidies, Antia explained.

“Inflation must be released in some way: it either drives down consumption in households, or it drives up fiscal deficits,” he said

As such, investors in emerging and frontier markets need to be aware of the countries that are particularly vulnerable: those where food makes up 30 to 40% of total household consumption.

Sovereign credit ratings don’t do justice to food security

Antia said investors should also pay attention to countries that are already slightly unstable politically: “a shock of food inflation can easily tip them over into something bigger that can really impact investors”, he warned.

Perhaps most importantly, investors need to consider whether the country is a major food exporter. “India is a major exporter of rice, so when India faces rice price pressures, they have a lever to pull that not all countries have,” he explained.

Earlier this year India banned exports of non-basmati white rice to tame rising domestic prices due to supply disruptions caused by inclement weather in the region.

This has already had ripple effects on the largely import-dependent Philippines, which has recently placed a cap on prices – something that has led to the resignation of a finance official who questioned the price decision.

As the world becomes less globalised and extreme climate events more frequent, disruptions to food supply chains are going to be more common, according to Antia.

“That means there are going to be more episodes that lead to food inflation and countries that are vulnerable to food inflation are going to face higher risks,” he said.

Despite these growing risks, his team at PGIM believes the standard sovereign credit ratings “don’t do justice to food security”.

“More episodes of food inflation mean more times governments have to step in and more fiscal funds are directed towards price supports,” he said.

“We are a bit of a turning point when it comes to food security. It’s going to be thrown on the radars of investors more frequently.”