Indian equities have been gaining traction among investors looking to diversify their emerging market exposure away from China towards other areas of growth.

Yet despite the growing appeal of the asset class, global investors remain hesitant to allocate to Indian equities over fears the market has become too richly valued.

Most investors considering an allocation to India often cite the premium of Indian equities relative to the wider emerging market average as a key factor.

This is according to Rohit Shimpi, a portfolio manager at SBI Funds Management – a joint venture between the State Bank of India (SBI) and French asset manager Amundi.

“It continues to be something that bothers virtually every prospect that we speak to and certainly existing investors in the fund,” he told FSA, describing the issue as the “elephant in the room”.

India’s stock market displayed surprising resilience during 2022 as many other developed market equity indices fell on the back of rising interest rates from central banks.

From the start of 2022, the MSCI India index is up 24.66% compared with the MSCI World and S&P 500 indices which are both roughly flat at 2.61% and 1.22% respectively (see chart 1).

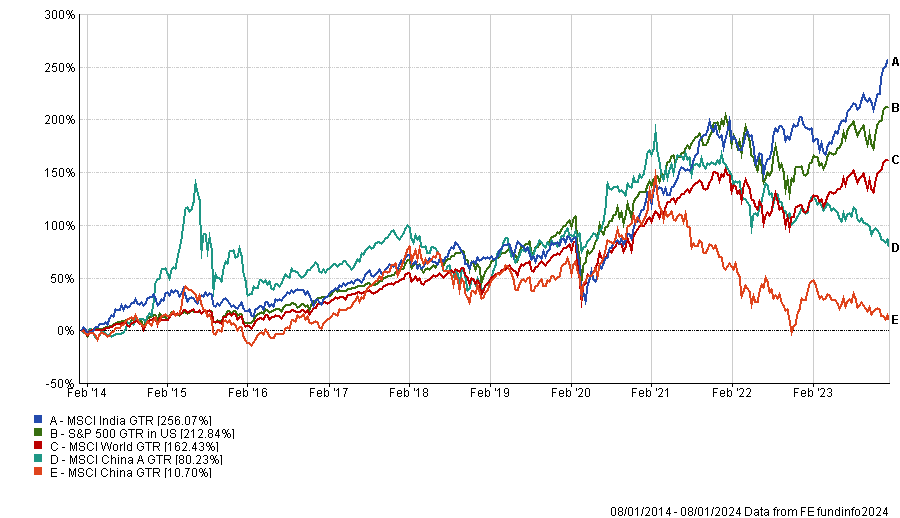

Over a longer timeframe of 10 years, Indian stocks have also outperformed the MSCI World, S&P 500 and MSCI China indices (see chart 2).

Chart 1:

Although Indian equities go through periods of short term over- and under-performance relative to wider emerging markets, Shimpi argued that valuations are not a good starting point in terms of determining which direction the market is going.

“We think it doesn’t have great predictive power in terms of whether India is going to underperform or outperform,” he explained.

“You have had instances in the past when it has been expensive relative to its history versus emerging markets and has done well over the next one year or three years.”

“You’ve seen the reverse as well, when the premium was lower relative to its history, at those points Indian markets have not necessarily outperformed emerging markets.”

Investors with a strong top-down view on India need to look under the hood of the equity market when considering allocating to the region, he said.

Chart 2:

“You can’t just find the lowest P/E stocks in the market and expect them all to perform all the time,” he said.

Instead, investors should go deeper and look at relative earnings growth, the quality of investment opportunities and the quality of management.

More broadly however, Shimpi thinks that the current valuation of the Indian equity market is supported by the fact that the earnings cycle has “decisively turned” during the past three years.

He said: “India had a poor setup for corporate earnings for the period between 2013 to 2020 due to a variety of reasons: the local and global economic slowdown that hit India, as well as lower commodity prices which meant certain companies in India were less comfortable.”

There was also the impact of the demonetisation of 2016 which saw 86% of India’s currency nullified to clean out counterfeit notes. It caused a stock market crash and widespread disruption in the economy.

“Covid was the last nail in the coffin in terms of earnings,” Shimpi said. “But quietly something was happening below the hood during Covid. Earnings started bouncing back sharply in 2021. On average, the CAGR of India’s earnings was as high as 20%.”

“In the initial couple of years, we think that it was driven a little bit by higher prices. It was not necessarily volume driven which is why there were sceptics who thought these were not high-quality earnings.”

“A stock picker’s paradise”

However throughout last year, the volume growth that would indicate better fundamental earnings started to emerge, Shimpi said.

“So cyclical sectors such as cement, real estate, capital goods and financials started seeing double digit growth; volume growth returned and that restored more confidence in earnings.”

“In that context, while valuations are high, if you have 20% earnings growth this year, and the consensus is for 15% earnings growth next year, we’re okay with that estimate because that give some comfort on valuations,” he said.

Despite the high level of topline growth that is expected from the wider Indian equity market, which itself should make the region relatively attractive when compared with other equity market regions, Shimpi said that the number of bottom-up opportunities emerging in the market is also very encouraging.

“A lot of investors have this very top-down view they want to take on India, but when you’re on the ground and meeting as many companies and reading as many annual reports as we do, there’s a lot of interesting bottom-up stories.”

“It feels like a stock pickers’ paradise in terms of the number of significantly sized companies that are available to analyse and potentially look at as an investor.”