An ongoing “corporate governance revolution” in an under researched equity market is making JPMorgan Japan’s lead manager Nicholas Weindling very optimistic about Japan.

“We have never felt so excited about the outlook for Japan as we do at the moment,” he said at a recent media roundtable in Hong Kong. “There is a corporate governance revolution going on in Japan.”

“The changes started about 10 years ago with a corporate governance code and a stewardship code, but the pace of those changes has really accelerated.”

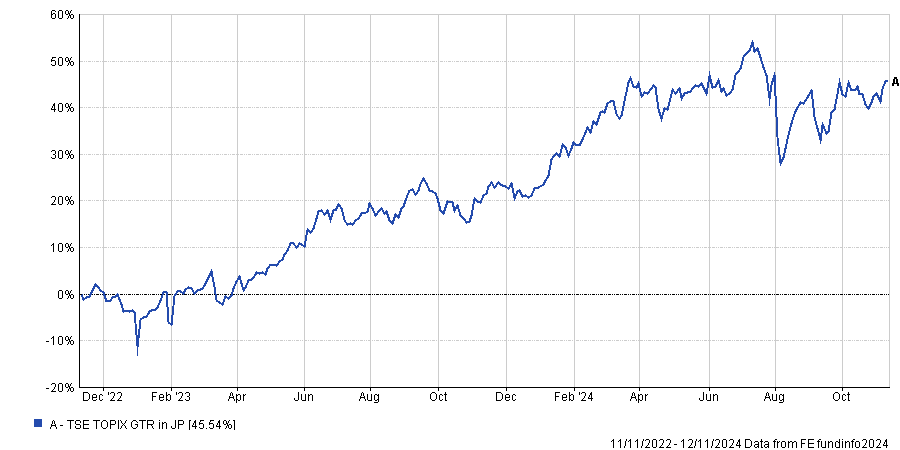

In early 2023 Japanese stocks broke out of a decades-long sideways market as corporate governance reforms put forward by the Tokyo Stock Exchange started to gain traction.

Yet despite a 45% rally over the past two years and a number of endorsements from foreign asset managers, including legendary value investor Warren Buffett, Weindling still thinks there is a long runway ahead for investors to benefit.

He pointed to a unified effort from multiple branches of government, including the Tokyo Stock Exchange and the Ministry of Finance to improve stock valuations in Japan.

Crucially, he said domestic asset managers are starting to vote more aggressively in AGMs and sometimes vote against management, which was previously unheard of.

“There’s also a generational change,” he said. “So many companies have much older managements who’ve been in place for a long time, and as they move to the next generation, we often see big changes in how they allocate capital.”

Strong fundamentals

Although some investors tend to focus on how weak demographics and a slow economy could weigh on the Japanese stock market, Weindling said it is important to remember there is a weak link between its economy and its listed companies.

“If you look at earnings per share growth in Japan since 2010 up until today, it is the same as it is for the S&P 500,” he said. “I think a lot of people find that quite shocking, that profit growth in Japan has been very, very strong.”

“There are many companies in Japan which are global number one, dominant at what they do, attractive companies growing their earnings but they just happen to be listed in Japan.”

Despite this, the Japanese equity market is still largely under researched and ripe for alpha, according to Weindling.

“Japan is a very under covered market,” he said. “There’s close to 4000 listed companies but over half of them have one or zero analysts writing about them.”

This has not been helped by the fact that foreign asset managers largely pulled out of Japan after the asset price bubble collapse in the 1990s and more recent Mifid II regulations weighing on equity research as a business model more generally.

Weindling hopes to take full advantage of the opportunity in Japan by finding “excellent companies” with “sub optimal” capital allocation.

“When I say sub optimal, I don’t mean that they have a weak balance sheet. In fact, I mean opposite. They have the extremely strong balance sheets,” he explained.

“They come in lots of sectors, but they are often more established companies because for historic reasons, they have all that cash.”

“A lot of owners have lived through the collapse of the bubble and at that time, Japanese banks were bankrupt – you couldn’t borrow money from them, so Japanese companies built up lots of cash so they could invest.”

He continued: “As that generation passes on to the next generation, they aren’t encumbered by this problem so much.”

One of JP Morgan’s largest positions is in Hitachi, a company that Weindling used to think they would be very unlikely to invest in due to the fact it is a huge conglomerate with low margins and many listed subsidiaries.

“Hitachi now have zero listed subsidiaries. They’re prioritising profitability, cash flow, and they are global top three in all of their five core businesses,” he said.

“There you’ve really seen earnings growth and rerating, when you get the two together. This is a very powerful combination.”