As the popularity of passive investing continues to rise, should investors think twice about building an investment strategy based on index funds?

Wei Dai, head of investment research at Dimensional Fund Advisors, seems to think it warrants closer scrutiny.

She said that many market indices are not necessarily created to be investment strategies with investment outcomes in mind.

Indeed, index giants S&P Global and MSCI have both admitted that fiduciary duty is fundamentally at odds with their role as index providers.

In 2022, the US securities and exchange commission (SEC) consulted the public on whether index providers should be regulated as investment advisors.

SEC Chair Gary Gensler said at the time: “The role of these information providers today raises important questions under the securities laws as to when they are providing investment advice rather than merely information.”

In their responses to the SEC, both S&P Global and MSCI argued that they are merely information providers, not investment advisors.

MSCI suggested that their products aren’t supposed to be the basis for an investment. In their own words: “index providers express no opinion or view as to whether any market, company, strategy or investment is good or bad, or appropriate or inappropriate”.

Meanwhile S&P Global argued that in creating indices, the company “makes no judgment of the merits of investing in the underlying constituents”.

Nevertheless, over $13trn is invested in passive portfolios tracking indices created by index providers, according to data from Morningstar.

Commenting on the index providers’ responses, Dai, whose firm runs $740bn in systematic active strategies, said: “I think it does call into question whether decisions are made for the best investment outcomes, or is there also consideration for whether the index will be popular and then tracked?”

An index created for wide ease of use, not investment outcomes

Since index providers are quick to point out they follow a publishing business model, it could create situations where their methodologies are influenced more by business considerations rather than investment outcomes.

A potential example of this can be seen when it comes to indices that are based on investment factors, such as those tracking the value, growth or momentum factors.

Dai points out that funds tracking a value factor-based index for example, can be subject to potential pitfalls in the index construction.

For many indices, she said there is a tendency to use a composite metric: “Let’s say there are five different value metrics, index providers may combine them in some way or maybe equal-weight it and then call it a day.”

“I call it a kitchen sink approach, and we don’t think that’s the best approach given that there’s a lot of noise in these metrics. It’s not a case of the more the merrier.”

Adding multiple value metrics to the investment process or index construction should increase the quality of the product, but Dai said it’s not often the case.

She explained: “You really need to know if the metrics you’re adding to the investment process, is truly giving you additional ability to identify higher expected returns?”

“Or is this just adding more noise and actually adding more moving parts? Because then that can lead to a lot of complexity and turnover which is not justified by higher expected returns.”

Some index providers add metrics to their index construction “mainly to just to capture what everybody else is doing,” she said.

Indeed, if it is a more relevant benchmark for active value managers, they will be more widely adopted and more fees will be paid to index providers – as per the publishing business model.

“I think it’s a fine rationale, but it’s not for the most effective capture of value,” Dai said. “It’s for making your indices more relevant and useful for more people to use it.”

Better outcomes for investors?

Investors can’t be blamed for favouring passive investing, seeing as the vast majority of active funds have failed to consistently beat the market and still charge hefty fees to do so.

Wealth managers and retail investors alike will find that passive investment products have been a cheap way to get exposure to the market and so-called ‘wisdom of the crowd’.

But as investors grow wary of the index concentration posed by the outperformance of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks, some are looking for alternatives such as value strategies to diversify risk.

Dimensional’s own version of index funds, known as systematic active funds, have a skew towards smaller companies and value stocks.

This is in Dai’s view, “the best way” to capture the value premium – the phenomenon where cheap stocks tend to outperform expensive ones over time.

“That by itself is not trivial to do,” she adds, because of how different index providers implement processes to capture ‘value’ and rebalance to avoid style drift.

She said: “You might actually get drastically different outcomes, even if they all sound like value funds.”

She points out that even for the same asset class within the same country, “there can be multiple indices representing those segments and you can get drastically different results”.

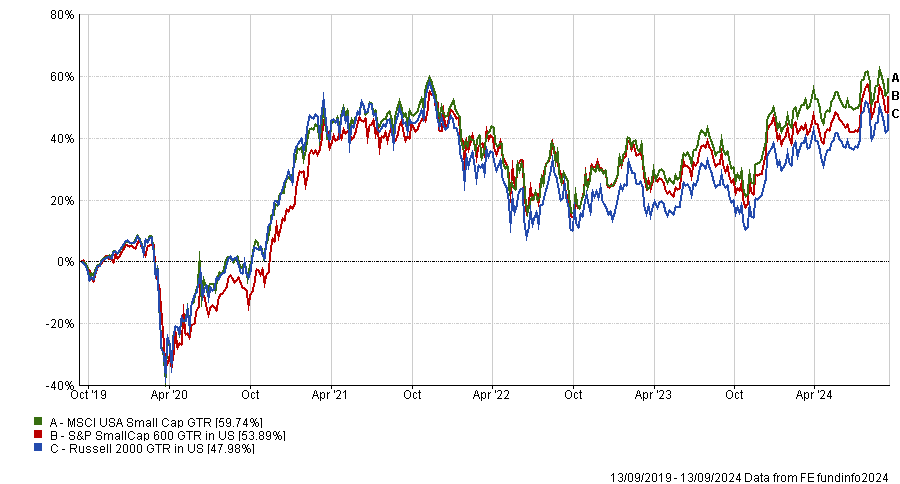

Indeed, when looking at the performance of US small caps for example, depending on which index benchmark used, there could be over 10% difference in return outcomes.

Over the past five years, the MSCI USA Small Cap index delivered 59.7% whereas the Russell 2000 index, delivered 48% over the same period.

The 11.7% difference between these two widely used US small cap benchmarks means that depending on the choice of index, investing in the same asset class resulted in roughly 25% higher returns. That’s as high as the difference seen between different asset classes.

“That data shows there’s a lot of decisions made by different indices that can impact the return experience,” Dai said.

That being said, she is quick to add that most investors are better off with investing in index funds and being able to access broadly diversified, low cost investments.

But she argues that Dimensional’s strategies are “not beholden” to any particular index, instead constructed with investment outcomes in mind.

“We define our own universe, do our due diligence on the countries and on individual stocks, whether they fit our investment criteria, and what that often means is we’re also able to go down lower in terms of market capitalization than the standard indices.”

“We do all of that due diligence ourselves in order to define our own market, because in the end, we think that we can do it in a more comprehensive way that’s more relevant for our investment goals.”