Despite improving fundamentals and an impressive rally over the past 12 months, Japanese equities are still neglected by many global active managers, according to GMO’s Drew Edwards.

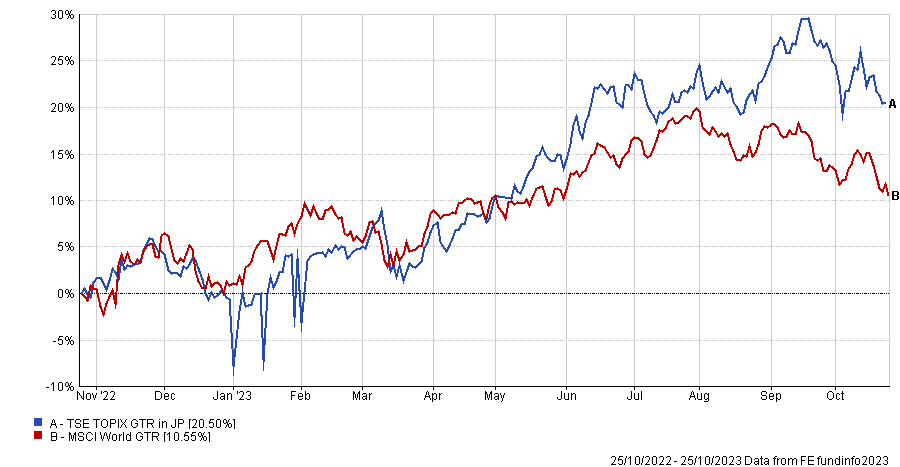

Over the past year, Japanese equities have been the best performing equity market among the major developed countries, more than doubling the returns of the wider MSCI World index.

Much of this performance has been attributed to the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s push for reforms aimed at setting a higher standard for corporate governance and shareholder-friendly behaviour from listed Japanese companies.

Yet despite an improving backdrop, many global investors are hesitant to commit to the region given its long history of poor corporate governance and stagnant returns over the 1990s and 2000s.

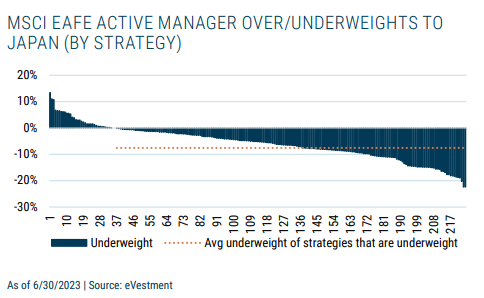

According to the research from GMO, most global equity strategies are still materially underweight Japanese equities as of mid-2023.

Of 225 actively managed strategies in the Nasdaq’s eVestment database that list the MSCI EAFE index (a global equity index that excludes the US and Canada) as their preferred benchmark, 84% are underweight Japan by an average of 7.5%.

Many active managers are underweight the region due to their firm’s structural issues and biases, rather than fundamental analysis, according to Drew Edwards, GMO’s head of Usonian Japan Equity.

After the burst of Japan’s asset bubble in 1989, international firms significantly cut their resources in the region as it entered a multi-year bear market and then stagnated for decades.

“To cover Japan, investment managers based in global financial centres, like New York and London, must endure extremely inconvenient logistical challenges, cultural challenges and idiosyncratic structural quirks of doing fundamental research and investing in Japanese equities,” Edwards said. “Most opted to allocate research resources to other markets.”

Active managers need to look beyond the nation’s history and acknowledge the change taking place in the equity markets, he argued.

“The point of gravity is not the 90s, not the 2000s, that was like the Great Depression in the US. You wouldn’t want to anchor the US on the Great Depression, there’s a lot more to the economy,” he said.

Improving fundamentals and governance reforms are becoming increasingly evident to Edwards and his investment team when they speak directly with companies and policymakers in Japan.

He compared the current situation in Japan to the that of the United States which had a company management-friendly stock market in the 1960s until the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974 was implemented and changed the outcome for investors.

Edwards said: “ERISA imposed fiduciary duties on institutional investors, it drove a rapid growth in assets managed by institutional investors, it changed the pension plan and took the percentage of ownership controlled by institutional investors from something like 10% to like 50%, and something like 80% now.”

He said a similar shift from a management-friendly stock market to a shareholder-friendly stock market is being introduced now in Japan and investors are starting to see the early phases of this change.

However historically, a volatile Japanese yen has been an issue for international investors, especially those in US-dollar focused institutions.

The depreciation has been made worse in more recent years by the Bank of Japan keeping interest rates low in comparison to the US Federal Reserve hiking rates close to 5%.

The Japanese currency has depreciated by roughly 30% over the past three years versus the US dollar, which would have offset any gains from any recent equity gains from active managers.

However, looking ahead, Edwards said it is an interesting time to be looking at Japan as an unhedged investor.

He said: “You have two ways to win: equity values don’t go up, but the currency strengthens, you win on the currency perspective, or conversely, yen remains weak and in aggregate, particularly manufacturers, do stand to benefit as a result of the weak yen.”